TORSON

ARCHIPELAGO / ONGLOING

A PALIMPSEST ON ART, ARCHITECTURE, POLITICS, MYTHOLOGIES, HISTORIES, GEOLOGY AND EVIRONNEMENTS.

According to the first known description of the Venetian lagoon, contained in the famous letter of Cassiodorus, addressed in 537-538 to the maritime tribunes, the Venetian region, dotted with islands, resembled the Cyclades. “Here”, wrote the powerful prefect of the Praetorium in his letter, “your house is made like that of the waterfowl, for what is now land sometimes appears to be an island, so much so that one believes oneself to be in the Cyclades when one suddenly sees again, unchanged, the aspect of the place1 “.

In the following centuries, the descendants of these lagoon populations succeeded, through a series of historical events, in creating the Serenissima Republic of Venice, one of the great medieval economic powers of the West. Taking advantage of the pseudo-crusade of 1204, the Venetians occupied “a quarter and a half” of the Byzantine territories and settled in most of the Aegean islands.

Thus, by a quirk of history, the inhabitants of the city of St Mark became masters of the Cyclades, of those islands whose landscape, according to Cassiodorus, resembled their lagoon. However, to designate Venice’s colonial empire in the Aegean, Venetian documents paradoxically use the name Arcipelago instead of the Greek name Aigaion Pelagos, which became familiar to navigators and in general to all Westerners.2

Because there have been so many terrible cataclysms in these nine thousand years - because there are so many years between then and now - the part of the earth that in these years and in so many accidents has been detached from the heights did not accumulate sediments of earth of a certain consistency, as in other places and, sliding down in a continuous process all around, disappeared in the depths of the sea [...].

Poseidon, having conceived her desire, joined forces with Cleitus and fortified the hill on which she lived, making it steep all around, forming alternating smaller and larger sea and land enclosures, one around the other, two on land, three on sea [...]. He fathered five pairs of sons and gave them all names, and to him who was the eldest and king he gave this name, which is the name of the whole island and sea, called Atlantic because the name of the first to reign then was Atlas.

Through archipelic thinking we can know the rocks of the smallest rivers for sure and envisage the water holes they cover where freshwater crayfish still shelter. The phrase act in your place, think with the world is now widespread. It can be found on the walls of the largest cities as well as on the traces of abandoned villages. With this remarkable injunction not to think in the world, which could reinvent the idea of conquest and domination, but to think with the world from which all sorts of relations and equivalences blossom.

First of all, place is inescapable because no one lives in suspension or dilution in the air, but also because I can never go around my place, contain it, bypass it, i.e. enclose it. The imaginary of my place is connected to the reality of all the places in the world. The archipelago is the image from which this imaginary arises. The scheme of belonging and relationship at the same time.

The archipelago is diffracted. We would go so far as to say with the practitioners of the chaos sciences that it is fractal. Necessary in its totality, fragile or possible in its unity. It is a state of the world.

Édouard Glissant,

Tout-Monde,

Paris,

Gallimard, 1993

1. ... ut illic magis aestimes esse Cycladas... : Magni Aurelii Cassiodori Variarum libri XII, cura et studio A. J. Fridh, Turnhout 1973 (Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 96), pp. 491-492.

2. Chryssa Maltezou, De la mer Égée à l’archipel : quelques remarques sur l’histoire insulaire égéenne Chryssa Maltezou p. 459-467, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 1998.

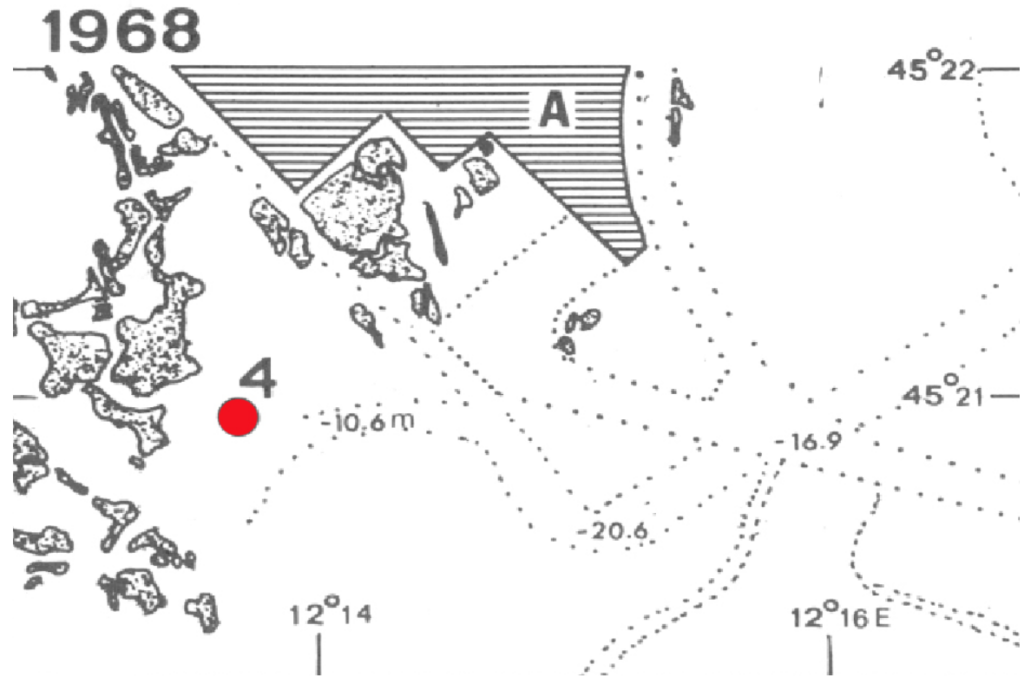

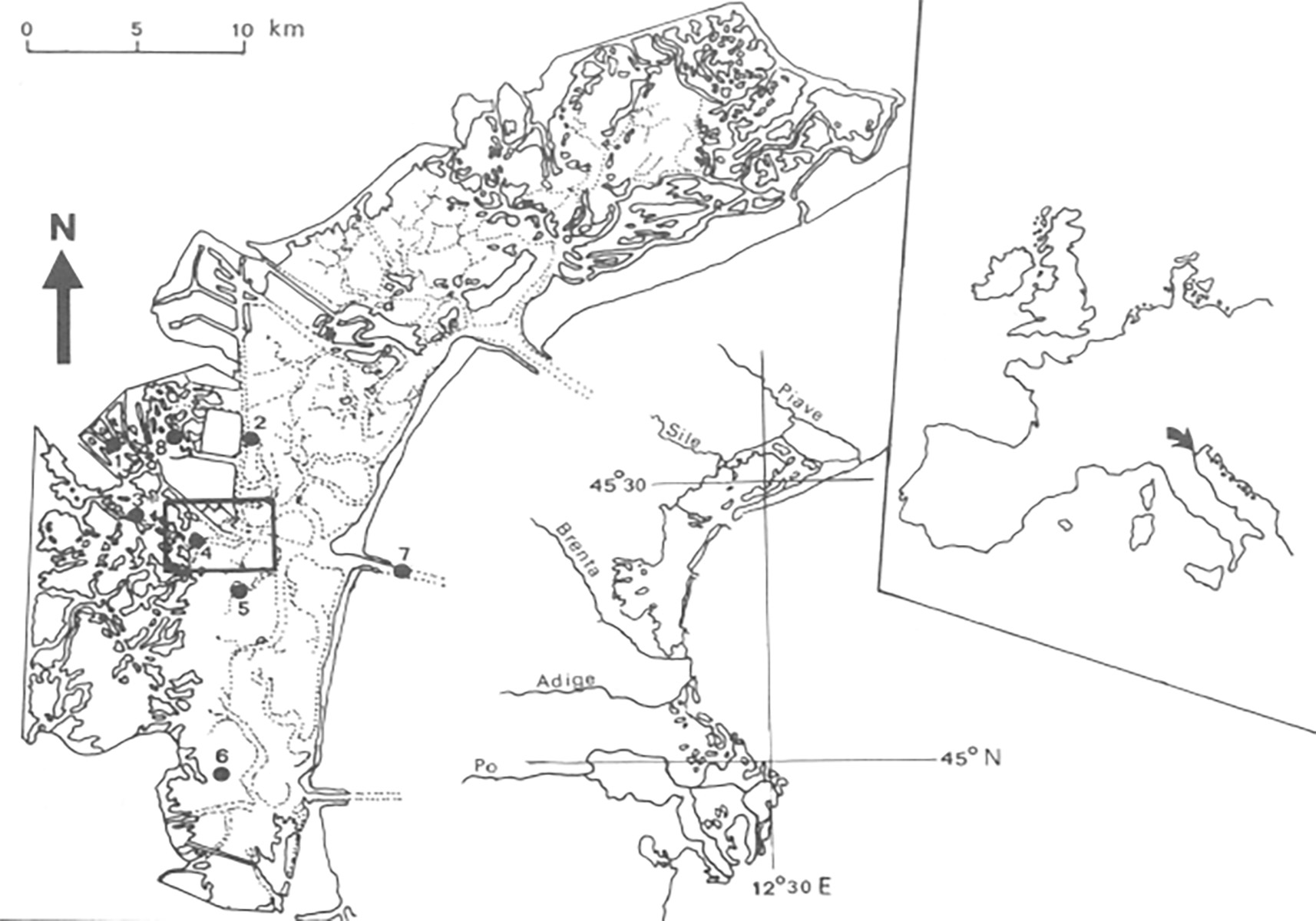

Engraulis encrasicolus (Sardone)

is a juvenile and seasonal marine

migrant in the Venetian Lagoon.

According to the first known description of the Venetian lagoon, contained in the famous letter of Cassiodorus, addressed in 537-538 to the maritime tribunes, the Venetian region, dotted with islands, resembled the Cyclades. “Here”, wrote the powerful prefect of the Praetorium in his letter, “your house is made like that of the waterfowl, for what is now land sometimes appears to be an island, so much so that one believes oneself to be in the Cyclades when one suddenly sees again, unchanged, the aspect of the place1 “.

Thus, by a quirk of history, the inhabitants of the city of St Mark became masters of the Cyclades, of those islands whose landscape, according to Cassiodorus, resembled their lagoon. However, to designate Venice’s colonial empire in the Aegean, Venetian documents paradoxically use the name Arcipelago instead of the Greek name Aigaion Pelagos, which became familiar to navigators and in general to all Westerners.2

Because there have been so many terrible cataclysms in these nine thousand years - because there are so many years between then and now - the part of the earth that in these years and in so many accidents has been detached from the heights did not accumulate sediments of earth of a certain consistency, as in other places and, sliding down in a continuous process all around, disappeared in the depths of the sea [...].

Through archipelic thinking we can know the rocks of the smallest rivers for sure and envisage the water holes they cover where freshwater crayfish still shelter. The phrase act in your place, think with the world is now widespread. It can be found on the walls of the largest cities as well as on the traces of abandoned villages. With this remarkable injunction not to think in the world, which could reinvent the idea of conquest and domination, but to think with the world from which all sorts of relations and equivalences blossom.

Édouard Glissant,

Tout-Monde,

Paris,

Gallimard, 1993